I am currently a Fine Art undergraduate, studying part-time at Bath Spa University in the UK, one of the members of the Global Academy of Liberal Arts (GALA) network. I went on a short placement to Namibia in late Summer 2025 with the aid of funding from GALA. I attended one of the other GALA partner universities – the University of Namibia (UNAM) in Windhoek – where I was enrolled on the Creative Arts undergraduate programme. I also spent several days in Twyfelfontein to see ancient rock art.

Twyfelfontein is in the north of Namibia, a five-hour drive from Windhoek. It is a desert region where the elephants are adapted to the sand with much wider feet. The arid climate has meant that rock carvings created by the San people several thousand years ago still survive. Although some have been destroyed by earthquakes and rockfalls, many are still visible. There is a designated visitor centre which almost all tourists visit, but I preferred walking through the landscape to see the ancient carvings in their natural setting, not fenced off. I also arranged to visit the Adam and Eve rock paintings. The guide did his best to discourage me, telling me that I would be disappointed as they are faded now and that no guest from the hotel had asked to visit them in three years. But I was not to be dissuaded, explaining that as an artist I wanted to get up close and feel a connection to this art created so long ago. So early one morning, before breakfast, the guide and I set off in a 1950’s Mercedes Unimog to visit the site. It is not fenced off – simply a large rock among many. It was a very special experience. While the painted human figures are weathered, you can still see that they are carrying a bucket between them. The mesh of a hunting net, a pair of ostriches, and an elephant still show on the rock surface after millennia, stubbornly resisting the ravages of wind and time. It was poignant, this echo of our forebears. The rock is flaking, and the paintings are unlikely to remain for much longer.

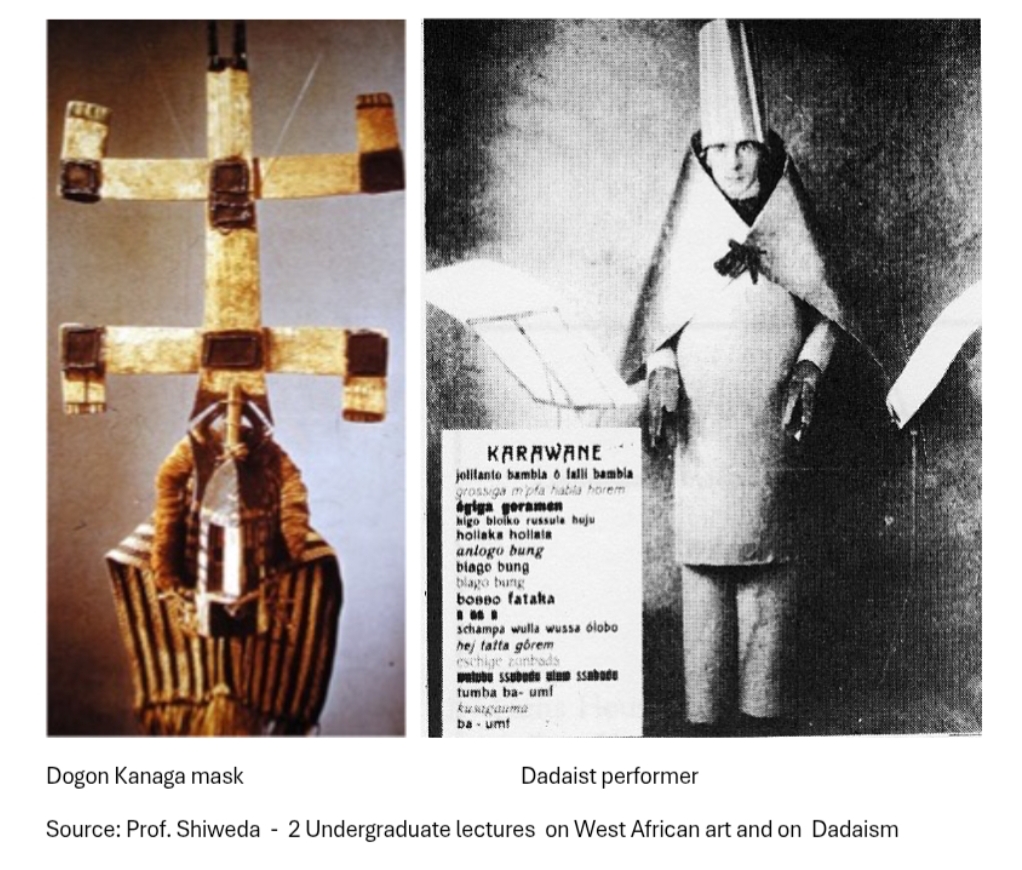

The staff at UNAM art department were welcoming. Professor Napundulwe Shiweda runs the Art History lecture programme, which I enjoyed greatly. There was a really good dialogue between the students and lecturer. They were studying Western art movements (I was disappointed to have missed the previous semester’s focus on African art, but Prof. Shiweda kindly downloaded her lectures onto a memory stick for me). Early on I expected to attend a lecture on Dadaism, a 1920s art movement typified by Marcel Duchamp’s submission of a mass-produced urinal to an exhibition as an artwork. When I got to UNAM, I was introduced as Paul Smith who is visiting us from Bath Spa university in the UK and will be giving us a lecture on his Art Practice and how it relates to Dadaism. I was briefly thrown, but had fortuitously read up on Dadaism in the taxi on the way in to UNAM, and I remembered that I had a PowerPoint of my studio art from a recent Bath Spa assignment that I quickly emailed to Prof. Shiweda. Luckily, I could relate my art to Dadaism as they share commonalities. It was interesting that the students’ initial response to both was that they placed a higher value on representational art over abstract, and technique over concept. They challenged me to explain and validate my art. Why did it have worth when it looked like a child had made it? What was the meaning behind it? Why had I chosen the apparently simple techniques and materials? I really enjoyed subsequent lectures from the Professor and engaging with the other students about their art.

I also enrolled on the Ceramics unit. I had previously worked with clay but not for several years. My art practice was now painting figures onto abandoned metal aircon pipes and blocks of wood. Transforming 2D works into a 3D object – so a flat painting is stretched around a tube or the paint surface ripped into to tear into our 3D world. Needing to use clay to represent the same challenged me. So, the flat surface of a rolled clay sheet was moulded and twisted to become a head in the round. But a head which appears as if a child made it. It perhaps invites ridicule for looking as if a child made it, with apparently little attempt at subtlety, but realism is not the aim: rather a sense of nostalgia while highlighting the fear and joy and sometime absurdity of life, made more apparent with the passage of time and an attendant sense of mortality. I explored the qualities of clay in my twice or thrice weekly sessions – its mouldability, reusability, tactility; the sense that it is an ancient material connecting us to our past.

I displayed 2 of my ceramic heads at the National Cultural Day at UNAM but quickly moved it on to the neighbouring display for the Sign Language club as it seemed to fit well there. They later survived the 5000-mile journey home travelling in Club class (albeit in an overhead locker) unlike me in Economy.

Thanks again to everyone at UNAM and Bath Spa University who helped make this happen. Hopefully some UNAM students will make the journey to Bath in the near future.